If you ever find yourself on solid ground, protect that with your life. Learn how it works and how to use it well. Then build a strong structure on top of that. Don't let it decompose into a layer of mud. (Precepts Discussion, C1)

A good place to begin our study of Arvo↗ is to considered the design intent to Urbit as a system:

Arvo is designed to avoid the usual state of complex event networks: event spaghetti. We keep track of every event's cause so that we have a clear causal chain for every computation. At the bottom of every chain is a Unix I/O event, such as a network request, terminal input, file sync, or timer event. We push every step in the path the request takes onto the chain until we get to the terminal cause of the computation. Then we use this causal stack to route results back to the caller.

You are likely familiar with the high-level concept of Arvo as an event handler and the main ratchet of the state machine.

$$ L: \text{History} \rightarrow \text{State} $$

Before we embark into Arvo, let's define some terms:

- A move is a “cause and action”. There is a formal

+$movetype that specifies the associated call stack and action. - An event is a completed move. The event results in an updated state, or subject for future computations. A completed event is recorded immutably in the event log history. Arvo itself doesn't know about the event log and history—it is amnesiac in the sense that it only computes against its current state.

Arvo is a pure function f(logs) of its event log, so formally Arvo is just a function run against an event log. A naive implementation has very bad asymptotics; processing each new event is O(n) in the number of historical events. Choose the function g(state,log) such that f(logs ++ log) = g(f(logs),log). Then, as long as you keep the state in memory, processing each new event is constant in the number of previous events. This still requires O(n) restart from disk, but you can also periodically (and non-blockingly) write a checkpoint of the state to disk, so that restart from disk is only linear in the number of events since the last checkpoint. (Precepts Discussion A11)

Guarantees

Solid-state. Specifically, Urbit is a solid-state interpreter. What is meant by that? If you search "solid-state interpreter", then Urbit is the answer, so it's not much help! “Solid state” refers to Urbit's grounded ability to acquire and specify state, as a unique, auditable, and reproducible basis for computing. An event, once committed to the log, is immutable and permanent, never lost.

Arvo's solid-statefulness differs from every major operating system in that no required information in the state of the OS is stored in RAM alone. (Incidentally, of course, the runtime uses RAM quite a lot, and a move being processed may be lost with a sudden shutdown.) This is one reason that Urbit is particularly write-heavy on hard drives, a consideration that hosting providers must take into account.

Interpreter. Urbit is an “interpreter” in the same sense that the Java Virtual Machine is an interpreter, only Nock serves the role of the Java bytecode. This means that it can receive a noun and update itself in situ.

Furthermore, Hoon is compiled and built continually throughout the lifetime of the process.

Atomic. Events

An interrupted event never happened. The computer is deterministic; an event is a transaction; the event log is a log of successful transactions. In a sense, replaying this log is not Turing complete. The log is an existence proof that every event within it terminates.

Consistency. Every update (completed event) leads to a new valid state.

Isolation. Events are performed sequentially, meaning that the effects are isolated. (See the “Breadth-First Move Ordering” section below.)

Durability. Completed events are permanent and immutable. No events will be reversed. But:

It is easy to think that "completed transaction will survive permanently" along with "the state of Arvo is pure function of its event log" implies that nothing can ever be deleted. This is not quite true. Clay is our referentially transparency file system, which could naively be thought to mean that since data must be immutable, files cannot be deleted. However, Clay can replace a file with a "tombstone" that causes Clay to crash whenever it is accessed. Referential transparency only guarantees that there won't be new data at a previously accessed location - not that it will still be available.

Arvo’s Structure

The beating heart of Arvo is a Nock expression, formally [%2 [%0 3] %0 2]. This means to evaluate the battery formula against the current subject to yield a new battery, then to evaluate that second battery against the subject produced from evaluating the payload against the current subject. In other words, to process the next event.

This is presented explicitly by the arm ++aeon, for instance, in the ++eden lifecycle formula generator. (The inline commentary there is worth reading in full; we'll see ++eden again in ca04.) Elsewhere it results operationally.

In most respects, tho, Arvo is an event processor. Most of the event processing and routing machinery is contained in /sys/arvo, with some plumbing on the vane-side as well.

+$ move [=duct =ball] :: CAUSE & ACTION::+$ duct (list wire) :: CAUSAL HISTORY::+$ ball (wite [vane=term task=maze] maze) :: see below+$ ball :: DYNAMIC KERNEL:: ACTION$? [%hurl [%error-tag stack-trace] wite=pass-or-gift] :: action failed[%pass wire=/vane-name/etc note=[vane=%vane-name task=[%.y p=vase]]]:: advance:: request[%slip note=[vane=%vane-name task=[%.y p=vase]]] :: lateral;:: make a request:: as though you're:: a different vane[%give gift=[%.y vase] :: retreat; response::+$ card (cask) :: tagged untyped:: event::++ cask |$ [a] (pair mark a) :: marked data:: builder::+$ meta (pair) :: meta-vase::+$ maze (each vase meta) :: vase or meta-vase

(There is some entanglement with particular vanes, which undercuts the simplicity of the system. It would be formally nice to refactor /sys/arvo into a pure statement of the event log without reference to vanes, which should be largely hypothetical to an event loop aside from routing labels. Cf. ~wicrum-wicrun on “Urbit is a ball of mud”↗. On the other hand, perhaps that loses efficiency. A question for a cooler kelvin.)

- A

+$moveis a cause and effect, simply a request to complete some task in a computation on behalf of the causal stack. Think of this as message data and history metadata. A move sends an action to a location along a call stack. - A

+$ductis a causal history, or the auditable chain of causes that leads to the current computation. - A

+$ballis an action. This is the part we conventionally think of as a computation: one of a%hurlfailure, a%passadvance, a%sliplateral move, or a%givereturn back down the causal chain. - A

+$cardis a tagged untyped event. (Notably, it is not+$card:agent:gall.) A card is an event of action. Cards can be arbitrarily complicated depending on the vane and message. - A

++caskis a marked data builder, commonly used to transmit data over the network (since vases are local only). - A

++metameta-vase is an untyped vase (e.g. a vase of vase). We'll see more of these in their+$mazeform.

If you read up on the runtime, at some point it used to refer to an “Arvo-shaped noun”. That means that the runtime expects to receive a core with certain arms, as this is how it will systematically interact with the noun it hosts.

Arvo defines four standard arms for vanes and the binary runtime to use:

++loadis used in kernel upgrades, allowing Arvo to update itself in-place, canonically at+4. (Formerly a++comearm was defined to assist in this procedure, targeting+$typechanges.)++wishaccepts a core and parses it against%zuse, which is instrumentation for runtime access, canonically at+10. (Seeca02.)++peekgrants read-only access to a vane; this is called a scry, canonically at+22.++pokeaccepts+$moves and processes them; this is the only arm that actually alters Arvo’s state, canonically at+23.

Each arm possesses the same structure, which means that as the Urbit OS kernel grows and changes the main event dispatcher can remain the same. For instance, when the build vane %ford was incorporated into %clay, no brain surgery was needed on Arvo to make this possible and legible. Only the affected vanes (and any calls to %ford) needed to change.

There's another wrinkle to the “simplicity” of Arvo: there are actually four Arvos in /sys/arvo:

- The larval core, used in building Arvo for the first time. We'll discuss this with the boot process in

ca04. - The structural interface core, the primary mature core, which is in operation for most of a ship's lifecycle and contains Arvo's state. It primarily calls out to the next two cores.

- The implementation core, the actual operational core carrying out particular computations and dispatches.

- The Section 3bE core, containing helper functions for Arvo that are sequestered for security and to maintain the four-arm prototype of Arvo. E.g., how to parse a scry path, how to negotiate versions, just Arvo's library code. Only pure functions, no state machines.

Urbit hews to the principle that “stateless is better than stateful” (Precepts A16). Most parts of the system are designed with the intent that they are stateless, or that any state is explicitly sequestered to a particular core. In Arvo, the state is the entire kernel in operation. There are persistent components (the Arvo state) and the ephemeral move worklists.

:: persistent arvo state::=/ pit=vase !>(..is) ::=/ vil=vile (viol p.pit) :: cached reflexives=| $: lac=_& :: laconic biteny=@ :: entropyour=ship :: identitybud=vase :: %zusevanes=(map term vane) :: modules== ::

- What is

!>(..is)doing here? It refers to the code above this point in Arvo as avase. vilis a cache of specific types—type,duct,path,vase. This saves on recompilation.lacis the verbosity dial (|verb).enyis the entropy.ouris the ship's identity.budis the stdlib.vanesis a list of vanes (more in a moment).

++wish and urbit eval

Is urbit eval just ++wish? Yes, it is—but it's not, in practice, any of the Arvo cores in /sys/arvo. In the king (the main process you'd run urbit eval through), it's actually an Arvo-shaped wrapper in /lib/vere which also sees Azimuth and Ethereum data. This is the outermost layer of the ivory pill (ca04).

Vanes & Move Handling

Vanes

Arvo is essentially an event router between heavyweight modules but including a stack discipline. (It's sort of like using a router to bind names to callback functions.) We need to consider two aspects of event processing:

- Kinds of moves

- Move mechanics

But first, what is Arvo routing moves between? Arvo contains in its state:

vanes=(map term vane)

where a +$vane is [=vase =worm]. (On which more later.) Arvo also stores a map from a name to a vase and a worm cache.

++ grow|= way=term?+ way way%a %ames%b %behn%c %clay%d %dill%e %eyre%g %gall%i %iris%j %jael%k %khan%l %lick==

A vane is ultimately a vase describing an outer gate which produces a core. The vane's state is that gate that wraps the core that has the right standard arms. Why a vase? Because all of this is going to be done explicitly in vase mode.

Eliding a lot of code, here is the skeleton of a vane, in this case Behn:

|= our=ship=> |%+$ behn-state$: %2timers=(tree [key=@da val=(qeu duct)])unix-duct=ductnext-wake=(unit @da)drips=drip-manager==--::=>=| behn-state=* state -|= [now=@da eny=@uvJ rof=roof]=* behn-gate .^?|%:: +call: handle a +task:behn request::++ call|= $: hen=ductdud=(unit goof)wrapped-task=(hobo task)==^- [(list move) _behn-gate]* * *:: +load: migrate an old state to a new behn version::++ load|= old=behn-state^+ behn-gate* * *:: +scry: view timer state::++ scry^- roon|= [lyc=gang pov=path car=term bem=beam]^- (unit (unit cage))* * *::++ stay state::++ take|= [tea=wire hen=duct dud=(unit goof) hin=sign]^- [(list move) _behn-gate]* * *

A vane exposes five standard arms:

++stayproduces the state of the vane.++loadmigrates the state of the vane.++callhandles an incoming task request.++takehandles a responsesign.++scryreturn the vane's state (as before a state migration).

Kinds of Moves

Arvo is an event loop, but until an event completes it is merely a move, a pair of cause and effect. Most of Arvo's work is done dispatching +$cards to and from vanes, which do the actual computation. From userspace, we are accustomed to seeing %pass and %gift Gall +$card:agent:galls. These are actually nerfed relative to Arvo +$moves, which contain more information. (They are laundered through ++wind.)

A %pass move is analogous to a call:

[duct %pass return-path=path vane-name=@tD data=card]

Arvo pushes the return path (preceded by the first letter of the vane name) onto the duct and sends the given data, a card, to the vane we specified. Any response will come along the same duct with the wire return-path.

A %give move is analogous to a return:

[duct %give data=card]

Arvo pops the top wire off the duct and sends the given card back to the caller.

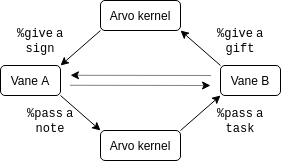

Each vane defines a protocol for interacting with other vanes (via Arvo) by defining four types of cards for its own namespace: tasks, gifts, notes, and signs.

When one vane is

%passed acardin itstask(defined inzuse), Arvo activates the+callgate with thecardas its argument. To produce a result, the vane%gives one of thecards defined in itsgift. If the vane needs to request something of another vane, it%passes it anotecard. When that other vane returns a result, Arvo activates the+takegate of the initial vane with one of thecards defined in itssign.

In other words, there are only four ways for Arvo and vanes to see a move:

- as a request seen by the caller, which is a

note. - that same request as seen by the callee, a

task. - the response to that first request as seen by the callee, a

gift. - the response to the first request as seen by the caller, a

sign.

What does a vane call look like? They are specific to each vane. The top-level type for a note looks like this:

+$ note-arvo :: out request $->$~ [%b %wake ~]$% [%a task:ames][%b task:behn][%c task:clay][%d task:dill][%e task:eyre][%g task:gall][%i task:iris][%j task:jael][%k task:khan][%l task:lick][%$ %whiz ~][@tas %meta vase]==

/sys/vane/behn defines the following interface in /sys/lull:

:: :::::::: ++behn :: (1b) timekeeping:: ::::++ behn ^?|%+$ gift :: out result <-$$% [%doze p=(unit @da)] :: next alarm[%wake error=(unit tang)] :: wakeup or failed[%meta p=vase][%heck syn=sign-arvo] :: response to %huck==+$ task :: in request ->$$~ [%vega ~] ::$% $>(%born vane-task) :: new unix process[%rest p=@da] :: cancel alarm[%drip p=vase] :: give in next event[%huck syn=sign-arvo] :: give back$>(%trim vane-task) :: trim state$>(%vega vane-task) :: report upgrade[%wait p=@da] :: set alarm[%wake ~] :: timer activate==-- ::behn

From Behn's perspective, it can receive a task or a gift. Anything sent to another vane is a note or a sign. So if you issue a call to Behn from Gall, the lifecycle looks like this:

- Agent sends vane-specific

cardto Gall ascard:agent:gall. - Gall

%passes anoteto Arvo through the++pokearm. - Arvo

%passes ataskto Behn through the++callarm. - When Behn wakes up on the timer, it

%gives a%giftto Arvo through the++pokearm. - Arvo

%gives asignto Gall through the++takearm. - Gall passes a

card:agent:gallto agent's++on-arvoarm.

Besides a %pass (forward) or %gift (reverse) move, there is also a %slip move.

A

%slipmoveis a cousin of%pass. Anycardthat can be%passed can also be%sliped, but while a%passsays to "push thiswireonto theductand transfer control to the receiving vane", a%sliptransfers control to the receiving vane without altering theduct. Therefore, a%givein response to a%slipwill go to the caller of the vane that sent the%sliprather than the vane that actually sent the%slip.%slips are much more rare than%passes and%gives. In general,%slipand%passmoves are both referred to as "passes" and it should be clear from the context if one means to refer only to%passes and not%slips or vice versa. Lastly, we note that%slipis a code smell and should nearly always be avoided. It can result in unexpected behavior like receiving a gift from a vane you never passed a note to.

In short, you %slip without pushing onto the ductso that control is given back to the top wire in the duct.

When is %slip preferred? It's not—it's typically code smell. Since it returns not to you but to your caller, it violates layering and breaks abstraction. In practice, it's not used much anymore, but it shows up in a few sensitive places like the subscription lifecycle, %init tasks (which only happen once in the lifecycle of each ship), and in a Clay-initiated Arvo upgrade. (Joe argues this is probably legacy functionality, and can likely be cleaned up after breadth-first move ordering is completed.)

The old docs refer to a %unix task, but this was always sort of ill-defined. %lull's '+$unix-task defines a subset of expected tasks, but the way vanes work now, the +$unix-task predicate is no longer needed so you don't think of it as a %unix task anymore. In actuality any arbitrary task can come in via conn.c. In practical terms %aqua (and likely %pyro) use this feature.

Exercise

- Produce a minimalist Arvo and vane system. This should look like three cores: an Arvo core which can handle the four basic move types; and two vanes (say

++loremand++ipsum) with minimalistgift/taskinterfaces and++call/++takearms. You can do this in a%saygenerator, for instance, or a/lib—don't worry about setting up a whole agent or modifying the kernel. (We'll build a vane later!)

Move Mechanics

Arvo basically only knows how to glue things together; in particular, it knows vanes by labels and simple interfaces alone. (See e.g. ++grow.) Arvo's formal state (thus Urbit's formal state) is always just to be a gate which operates on an event to produce the next state.

+$ vane [=vase =worm]

A vane is a vase and a worm. The vase encompasses the type and the noun of the vane. Vanes are compiled with %zuse as their subject (thus the other inner cores as well).

Vanes operate in vase mode. Any vane call is a +slap in vase mode. For instance, vanes can emit cards or metacards, a vase of a card. The ++va and ++wa engines assist with operating vanes.

Aside: Metacards & ;; micmic

The vane interface is normally strictly typed, but using a metavase it can punch a hole through the type system. (This used to be the only way to do vase reduction before !< zapgal was introduced: a vane had to pass to Arvo to get into double vase mode, which Arvo would collapse into one vase mode and hand back.)

Urbit core developers used to be more cautious about molding data. The mold system in particular was a total system prior to the introduction of structure mode in 2018: if the input mismatched, the mold would bunt (so the correct type was always returned). (Joe describes the mold system at this point as “a pile of hacks”.) If you knew the type, you could mold a value quickly to make it a static value.

Since molds would bunt on input mismatch, you needed to have a fixed-point assertion that guaranteed validation, thus ;; micmic. After the introduction of structure mode (“spec mode”) changes, molds crash if they fail (rather than bunting). So the primary reason ;; micmic still exists is the easy of entering parser mode:

> (,[%foo %bar] [%foo %bar])[%foo %bar]> ;;([%foo %bar] [%foo %bar])[%foo %bar]

Other than that, it is essentially superfluous in contemporary Hoon.

++va: Vane Operations

Vanes have a definite interface as described above. ++va is an engine for interacting with them. So the ++va core is for actually running vanes. It accepts +$mazes as input (like the ++call arm, which advances the vane state). ++va is basically a workhorse to handle vane transactions and there's not a lot to say about it as a vane.

E.g. ++plow is the sole arm of an inner core, designed to “operate in time and space” on a vane. It is a gate which attaches a rook (meta-namespace) to an Arvo-side interface for a vane and evaluates the vane within that namespace.

Although not in ++va, a related gate is the ++look arm in the Section 3bE Arvo core. Each vane receives a +$roof in its function call which it can call when it needs to scry. ++look converts into a ++mink-compatible version, acting as a bridge between .^ dotket and the scry handler (++look) with access to the roof that came from the vane. This pattern imposes constraints on interpreters, but if you just gave agents a scry handler then its a gate closed over the entire vane state so one could access anything in any vane state. Thus .^ dotket gives mediated access so you don't reveal state of the entire system in the subject (untyped permissions-free access). This uses the ++wa interface (below) but doesn't cache because it's a stateful function, mold and path hoon compiler turns mold into a type and you get an untyped nest-check on the result. (This is where scry-lost comes from.) ~mastyr-bottec will ultimately replace this in-Arvo stateful cache with persistent memoization in the runtime.

++wa: worm Cache

All vane calls are fundamentally a +slap in vase mode, so formally Arvo runs the compiler all the time. To help with this, there's a worm cache to help speed that up. Thus ++wa is where first-time computations are initiated and then stored in the cache. (The worm cache is part of Arvo's state; where did that slip in through the definition we had above?)

The worm cache is manual memoization in the dumbest possible way.

+$ worm$: :: +nest, +play, and +mint::nes=(set ^)pay=(map (pair type hoon) type)mit=(map (pair type hoon) (pair type nock))==

nesis s set of pairs of types that nest. (I.e., if it's in the set then it nests.)payis a map oftypeandhoontotype.mitis a map oftypeandhoontotypeandnock.

There are no faces so lark notation is used throughout ++wa.

Each call to a vane falls into one of three categories:

- Cached: produce

%.yandwa-cache. - Not cached and failed

nest-check: produce a manualprintf. - Not cached and succeeded

nest-check: produce%.nandwa-cache.

In Arvo, a lot of pieces have to be done manually. For instance, ++open:wa is a manual %~ censig on a door. (Joe points out that ++wa is currently a messy core because half of the operations are on vases and half are on mazes.) You have to operate untyped throughout:

++slurcalls++neatinstead of++nest++neatis eithervaseormaze, and calls++netsinstead of++nestbecause it is untyped, then makes thenest-checkwith++slum(an untyped++slamworking on a rawnock).- E.g. when Arvo runs the

++scryarm of a vane, it receives back avaseof(unit (unit cage))so there are multiple layers of nesting. This needs a sort of manual!<zapgal, not actually promoting into a type but still operating on it. (Both of these methods are hacks, but this is less dangerous (only true because vanes are trusted), whereas!<zapgal is a type hole implicating the whole system.) - The other time we construct these is when we get raw events (any

+$ovum).

Arvo maintains a worm cache for each vane, built when initializing. Ultimately this should be changed to runtime memoization instead. That will allow arbitrary associative memory (and presumably constant-time lookup), but these are currently double-++mug balanced treaps.

Runtime Connexions

Two functions are of particular interest in beginning to see how the runtime handles an event: u3_serf_work, which applies events and produces effects; and u3v_poke_sure, which injects an event and saves the new state if successful.

We'll see more about this in ca05 when we look at the structure of Vere.

Breadth-First Move Ordering

Planned for the future is breadth-first move ordering (current PR↗). What does this mean? (Much of this section quotes ~wicdev-wisryt's #6041 PR↗ description.)

Arvo currently orders moves by depth first. Visually, when evaluating depth-first an event may look like this:

["" %unix %belt /d/term/1 ~2022.10.27..06.32.09..30db]["|" %pass [%dill %g] [[%deal [~zod ~zod] %hood %poke] /] ~[//term/1]]["||" %give %gall [%unto %poke-ack] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["||" %pass [%gall %g] [[%deal [~zod ~zod] %dojo %poke] /use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/drum/phat/~zod/dojo] ~[/dill //term/1]]["|||" %give %gall [%unto %poke-ack] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["||||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["|||||" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.efXKi/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||||" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.efXKi/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||||" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.efXKi/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["||||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["|||||" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.efXKi/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["|||" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.efXKi/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]

The breadth-first equivalent looks like this:

["" %unix %belt /d/term/1 ~2022.11.2..00.18.15..ce5b]["1" %pass [%dill %g] [[%deal [~zod ~zod] %hood %poke] /] ~[//term/1]]["11" %give %gall [%unto %poke-ack] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["12" %pass [%gall %g] [[%deal [~zod ~zod] %dojo %poke] /use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/drum/phat/~zod/dojo] ~[/dill //term/1]]["121" %give %gall [%unto %poke-ack] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["122" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["123" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["124" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["125" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/gall/use/hood/0w2.Rh6DI/out/~zod/dojo/1/drum/phat/~zod/dojo t=~[/dill //term/1]]["1221" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["1231" %give %gall [%unto %fact] i=/dill t=~[//term/1]]["12211" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.Rh6DI/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["12213" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.Rh6DI/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["12215" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.Rh6DI/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]["12311" %give %dill %blit i=/gall/use/herm/0w2.Rh6DI/~zod/view/ t=~[/dill //term/1]]

These are the same 15 lines, and they're each at the same depth, but they're in a different order. Most code we write is agnostic to this order, because there are many circumstances where this order gets inverted compared to our expectations.

The most obvious difference is that the four %facts from %dojo to %hood happen one right after the other instead of being mingled with other moves. If some of those intermingled moves invoked dojo (which would be a form of reentrancy) and caused dojo to emit more facts, those facts would be given to hood before the %facts which were already on the stack to be sent to hood. If this is textual output, then it will be in reverse order. The breadth-first move order fixes this problem completely by running all the facts that were issued at the same time before processing the moves that those themselves produced.

This leads to a very important principle: breadth-first ordering guarantees that moves will be processed in the order they are emitted. Depth-first ordering constantly violates this, and in the presence of reentrancy this can cause extremely unexpected results.

(The #6041 PR↗ elaborates on the motivation for the current depth-first ordering.)

Depth-first ordering will be deprecated in favor of breadth-first ordering, which should make the issuance of multiple cards more transparent to reason about.

he actually emailed me the other day (i haven't communicated with him in years) to exhort me to reject the breadth-first move ordering pr, and we had a little back-and-forth. he still believes you can use moves essentially as function calls, and if you just add enough queues to random places, it'll all work out cleanly, like adding epicycles

Exercise

- Follow a move trace. Type

|verbinto Dojo, followed by+ls %. The system will respond with a verbose description of how the move was processed. (Since the system will produce more output in response to subsequent events, it's easiest to copy this into a text editor for review.) You can turn|verboff again as a toggle. There is also an annotated move trace you can read for more perspective.

OTAs

How does an over-the-air (OTA) update work? Essentially we transmit a noun to Arvo describing the new state and update (transition) rules. In practice, there are three possibilities when an upgrade command is sent to Arvo as a task using ++what, picking the Hoon source out of the list there:

- No-op: empty list or the same version.

- No Arvo change: just an upgrade of vanes or stdlib (

%lull/%zuse). - New Arvo kernel, up to and including a language change.

Any time you need your code to be flexible for future upgrades, you have to be inflexible about a few things—but as few as possible. The Arvo upgrade process is intended to constrain future Arvo as little as possible.

Arvo knows about /sys and the relative precedence of %hoon/%arvo/%lull/%zuse/vanes so it can rebuild based on the topology of changes. If only %lull/%zuse/a vane are different, then you only need to build the new cores and provide them as inner cores for the new system. If, on the other hand, %hoon or %arvo are different, then we need to build the new /sys/hoon, compile the new /sys/arvo, then gather all persistent and ephemeral state plus the new upgrade state and hand that to the new %arvo core. (If Arvo itself changes, then it tries to get into the new world as quickly as possible.)

This is an area where depth-first v. breadth-first move ordering makes a difference. Current DFMO means there is always a worklist to pass to the new Arvo, because there may still be moves to run. This acts as a constraint on new vanes because they may have to handle old-world moves still. BFMO means there will be more flexibility.

Concretely, once you learn a new revision exists, you tell Clay to merge the desks. Clay talks to the publisher over Ames to retrieve the metadata, then requests the individual files using Fine (fee-NAY), the remote scry protocol. (In essence, this allows the subscribers to check out the desk updates to %base directly from the serving runtime rather than needing to request to the server's Arvo.) With that data, the commit process starts. This is handled by ++park in Clay.

++park has some state for the pending blob store &c. Then ++sys-update is called, which sends the move to Arvo with all source code for the new commit. A blob is a content-addressed store of data. This is one place where %slip comes in handy: Clay %slips a %pork to itself to trigger the continuation, so once Arvo is done upgrading, the next thing for Arvo to run is Clay with an empty %pork task—thus Clay goes right back into the same arm and continues where it left off in the commit process.

One place complications arise is with +$type, since a change to +$type impacts vase mode handling.

Some subtleties regarding types arise when handling OTA updates, since they can potentially alter the type system. Put more concretely, the type of

typemay be updated. In that case, the update is an untyped Nock formula from the perspective of the old kernel, but ordinary typed Hoon code from the perspective of the new kernel. Besides this one detail, the only functionality of the Arvo kernel proper that is untyped are its interactions with the Unix runtime.

Some particular details of an Arvo upgrade will be discussed later, since ultimately, OTA upgrades to Arvo have much in common with the boot process—next week's lesson, ca04, covers a new ship's boot process.

Homework

- Annotate a move trace. Produce a move trace, such as from a generator invocation like

|pass [%d %text "foo"]. Comment line-by-line on what is happening. (Some lines, like repeated%hoodcalls, can be grouped.) You can turn verbose logging off again using|verbto toggle. - Produce a functional minimalist Arvo to boot on Vere. You need to make a gate that produce a core with four arms, each returning a gate with the correct type signature. (

/sys/arvocan see all of/sys/hoon.) This should be built into a new boot pill,baby.pill. Phil walks through this whole process in this video↗. You could%sloginput on a vane no-op.