Writing Jets

Many operations are inefficient when implemented in Nock, and it is efficacious to treat Nock as a standard of behavior rather than the implementation. This tutorial aims to teach you how to read existing jet code; produce a jet matching a Hoon gate with a single argument; and produce a more complex jet involving multiple values and floating-point arithmetic. It will then discuss jetting more generically.

Since jetting code requires modifying the binary runtime, we will work some in Hoon but much more in C. While you can build whatever you like as experimental or personal work, if you intend to submit your jetted code back to the main Urbit developer community then you should coordinate with the Urbit Foundation.

Additional Resources

- ~timluc-miptev, “Jets in the Urbit Runtime”↗ (recommended to start here first)

- “

u3: Land of Nouns” (recommended as supplement to this document) - “API overview by prefix” (recommended as supplement after this document)

Developer Environment

Basic Setup (Mise en place)

All of Urbit's source code is available in the main Github repo. We will presumptively work in a folder called ~/jetting which contains a copy of the full Urbit repo. Create a new branch within the repo named example-jet.

$ cd$ mkdir jetting$ cd jetting$ git clone https://github.com/urbit/vere.git

The Urbit runtime build stack is based on Bazel↗. This suffices unless you intend to include some other third-party library, which must be linked statically↗ due to how the Urbit binary is distributed. There is also a bias towards software implementations of processes which hew to a specified reference implementation, such as SoftFloat↗ rather than hardware floating-point for IEEE 754↗ floating-point mathematics.

Since jet development requires booting ships many times as one iterates, a pill can make the Urbit-side development process much faster, and is actually required for kernel jets.

Test your build process to produce a local executable binary of Vere:

$ cd ~/jetting/vere$ bazel build :urbit

This invokes Nix to build the Urbit binary. Take note of where that binary is located (typically in /tmp on your main file system) and create a new fakezod using a downloaded pill. (You should check the current binary version and use the appropriate pill instead of v1.9.)

$ cd ~/jetting$ wget https://bootstrap.urbit.org/urbit-v1.9.pill$ <Nix build path>/bin/urbit -B urbit-v1.9.pill -F zod

As you work through this guide, version numbers will likely be older than the contemporary release version due to the pace of release. We will update this guide if a version breaks the instructions.

We will primarily work in the development ship (a fakeship or moon) on the files just mentioned, and in the pkg/urbit directory of the main Urbit repository, so we need a development process that allows us to quickly access each of these, move them into the appropriate location, and build necessary components. The basic development cycle will look like this:

- Compose correct Hoon code.

- Hint the Hoon code.

- Register the jets in the Vere C code.

- Compose the jets.

- Compile and troubleshoot.

- Repeat as necessary.

Conveniences

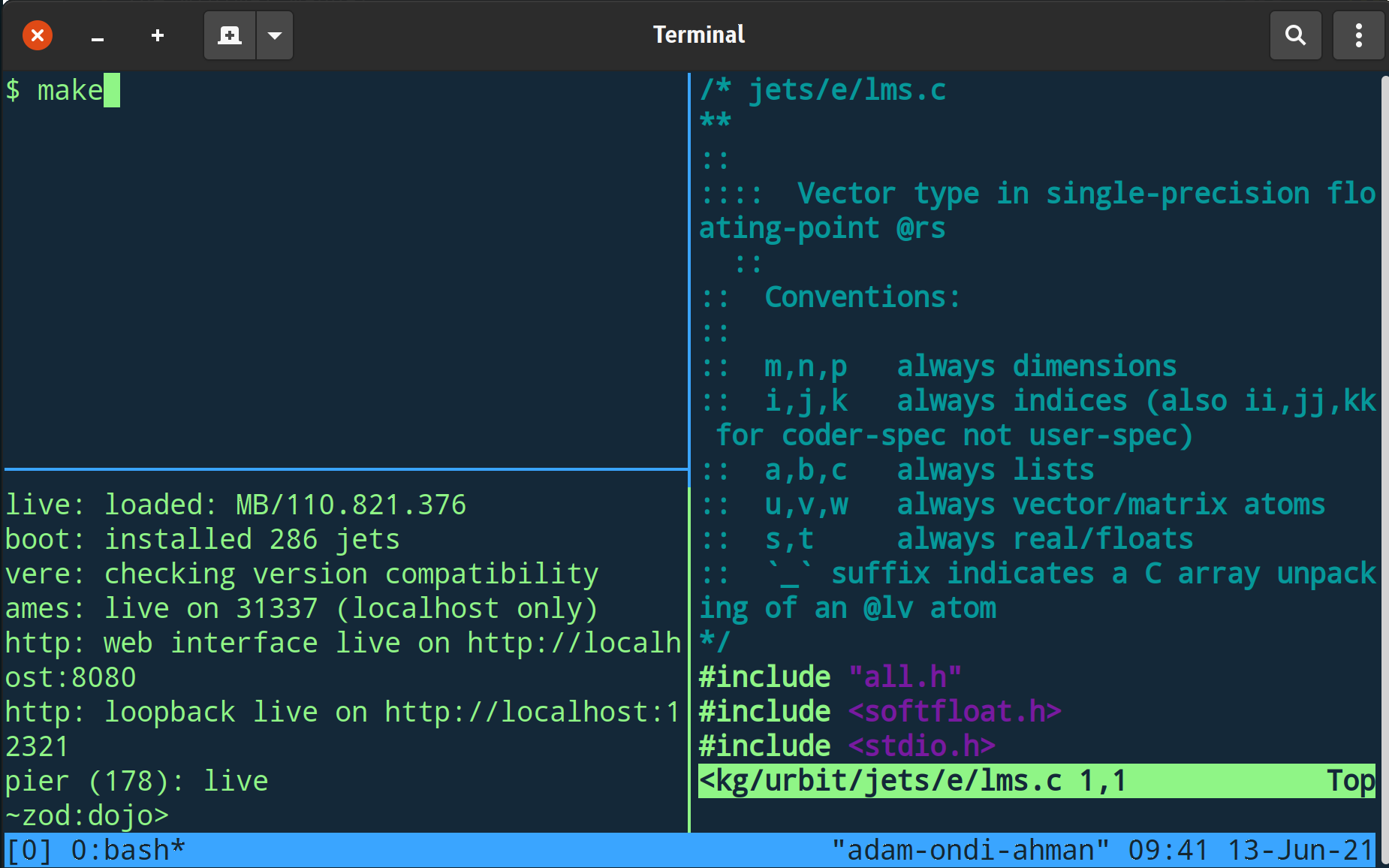

You should consider using a terminal utility like tmux or screen which allows you to work in several locations on your file system simultaneously: one for file system operations (copying files in and out of the home directory), one for running the development ship, and one for editing the files, or an IDE or text editor if preferred.

Inside of your development ship, sync %clay to Unix,

> |mount %

Then copy the entire %base desk out so that you can work with it and copy it back in as necessary.

$ cp -r zod/base .

In addition, making a backup copy of a fakeship will make it much faster to reset if memory gets corrupted. (This is regrettably common when developing jets.)

$ cp -r zod zod-backup

To reset, simply delete the .urb/ directory and replace it:

$ rm -rf zod/.urb$ cp -r zod-backup/.urb zod

Jet Walkthrough: ++add

Given a Hoon gate, how can a developer produce a matching C jet? Let us illustrate the process using a simple |% core. We assume the reader has achieved facility with both Hoon code and C code. This tutorial aims to communicate the practical process of producing a jet, and many u3 noun concepts are only briefly discussed or alluded to.

To this end, we begin by examining the Hoon ++add gate, which accepts two values in its sample.

The Hoon code for ++add decrements one of these values and adds one to the other for each decrement until zero is reached. This is because all atoms in Hoon are unsigned integers and Nock has no simple addition operation. The source code for ++add is located in hoon.hoon:

|%+| %math++ add~/ %add:: unsigned addition:::: a: augend:: b: addend|= [a=@ b=@]:: sum^- @?: =(0 a) b$(a (dec a), b +(b))

or in a more compact form (omitting the parent core and chapter label)

++ add~/ %add|= [a=@ b=@] ^- @?: =(0 a) b$(a (dec a), b +(b))

The jet hint %add allows Hoon to hint to the runtime that a jet may exist. By convention, the jet hint name matches the gate label. Jets must be registered elsewhere in the runtime source code for the Vere binary to know where to connect the hint; we elide that discussion until we take a look at jet implementation below. We will expand on the jet registration runes ~/ sigfas and ~% sigcen later.

The following C code implements ++add as a significantly faster operation including handling of >31-bit atoms. It may be found in urbit/pkg/noun/jets/a/add.c:

u3_nounu3qa_add(u3_atom a,u3_atom b){if ( _(u3a_is_cat(a)) && _(u3a_is_cat(b)) ) {c3_w c = a + b;return u3i_words(1, &c);}else if ( 0 == a ) {return u3k(b);}else {mpz_t a_mp, b_mp;u3r_mp(a_mp, a);u3r_mp(b_mp, b);mpz_add(a_mp, a_mp, b_mp);mpz_clear(b_mp);return u3i_mp(a_mp);}}u3_nounu3wa_add(u3_noun cor){u3_noun a, b;if ( (c3n == u3r_mean(cor, u3x_sam_2, &a, u3x_sam_3, &b, 0)) ||(c3n == u3ud(a)) ||(c3n == u3ud(b) && a != 0) ){return u3m_bail(c3__exit);} else {return u3qa_add(a, b);}}

The main entry point for a call into the function is u3wa_add. u3w functions are translator functions which accept the entire sample as a u3_noun (or Nock noun). u3q functions take custom combinations of nouns and atoms and generally correspond to unpacked samples.

u3wa_add defines two nouns a and b which will hold the unpacked arguments from the sample. The sample elements are copied out by reference into a from sample address 2 (u3x_sam_2) and into b from sample address 3 (u3x_sam_3). A couple of consistency checks are made; if these fail, u3m_bail yields a runtime error. Else u3qa_add is invoked on the C-style arguments.

u3qa_add has the task of adding two Urbit atoms. There is a catch, however! An atom may be a direct atom (meaning the value as an unsigned integer fits into 31 bits) or an indirect atom (anything higher than that). Direct atoms, called cats, are indicated by the first bit being zero.

0ZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ.ZZZZ

Any atom value which may be represented as $2^{31}-1 = 2.147.483.647$ or less is a direct atom. The Z bits simply contain the value.

> `@ub`2.147.483.6470b111.1111.1111.1111.1111.1111.1111.1111> `@ux`2.147.483.6470x7fff.ffff

However, any atom with a value greater than this (including many cords, floating-point values, etc.) is an indirect atom (or dog) marked with a prefixed bit of one.

11YX.XXXX.XXXX.XXXX.XXXX.XXXX.XXXX.XXXX

where bit 31 indicates indirectness, bit 30 is always set, and bit 29 (Y) indicates if the value is an atom or a cell. An indirect atom contains a pointer into the loom from bits 0–28 (bits X).

What does this mean for u3qa_add? It means that if the atoms are both direct atoms (cats), the addition is straightforward and simply carried out in C. When converted back into an atom, a helper function u3i_words deals with the possibility of overflow and the concomitant transformation to a dog.

c3_w c = a + b; # c3_w is a 32-bit C word.return u3i_words(1, &c);

There's a second trivial case to handle one of the values being zero. (It is unclear to the author of this tutorial why both cases as-zero are not being handled; the speed change may be too trivial to matter.)

Finally, the general case of adding the values at two loom addresses is dealt with. This requires general pointer-based arithmetic with GMP multi-precision integer operations↗.

mpz_t a_mp, b_mp; # mpz_t is a GMP multi-precision integer typeu3r_mp(a_mp, a); # read the atoms out of the loom into the MP typeu3r_mp(b_mp, b);mpz_add(a_mp, a_mp, b_mp); # carry out MP-correct additionmpz_clear(b_mp); # clear the now-unnecessary `b` value from memoryreturn u3i_mp(a_mp); # write the value back into the loom and return it

The procedure to solve the problem in the C jet does not need to follow the same algorithm as the Hoon code. (In fact, it is preferred to use native C implementations where possible to avoid memory leaks in the u3 noun system.)

In general, jet code feels a bit heavy and formal. Jet code may call other jet code, however, so much as with Hoon layers of complexity can be appropriately encapsulated. Once you are used to the conventions of the u3 library, you will be in a good position to produce working and secure jet code.

Jet Composition: Integer ++factorial

Similar to how we encountered recursion way back in Hoon School to talk about gate mechanics, let us implement a C jet of the ++factorial example code. We will call this library trig in a gesture to some subsequent functions you should implement as an exercise. Create a file lib/trig.hoon with the following contents:

/lib/trig.hoon

~% %trig ..part ~|%:: Factorial, $x!$::++ factorial~/ %factorial|= x=@ud ^- @ud=/ t=@ud 1|- ^- @rs?: =(x 0) t?: =(x 1) t$(x (sub x 1), t (mul t x))--

We will create a generator gen/trig.hoon which will help us quickly check the library's behavior.

/gen/trig.hoon

/+ *trig!::- %say|= [[* eny=@uv *] [x=@rs n=@rs ~] ~]::~& (factorial n)~& (absolute x)~& (exp x)~& (pow-n x n)[%verb ~]

We will further define a few unit tests as checks on arm behavior in tests/lib/trig.hoon:

/tests/lib/trig.hoon

/+ *test, *trig::::::::|%++ test-factorial ^- tang;: weld%+ expect-eq!> 1!> (factorial 0)%+ expect-eq!> 1!> (factorial 1)%+ expect-eq!> 120!> (factorial 5)%+ expect-eq!> 720!> (factorial 6)==--

(Here we are eliding a key point about contemporary Urbit development: /lib code is considered userspace and thus ineligible for jet inclusion in the runtime. This is a matter of development policy rather than technical capability. We will zoom out to consider how to modify kernel code later.)

Save the foregoing library code in base/lib and the generator code in base/gen; also, don't forget the unit tests! Whenever you work in your preferred editor, you should work on the base copies, then move them back into the fakezod and synchronize before execution.

$ cp -r base zod

> |commit %base> -test %/tests/lib/trig ~built /tests/lib/trig/hoonOK /lib/trig/test-factorial

Jet construction

Now that you have a developer cycle in place, let's examine what's necessary to produce a jet. A jet is a C function which replicates the behavior of a Hoon (Nock) gate. Jets have to be able to manipulate Urbit quantities within the binary, which requires both the proper affordances within the Hoon code (the interpreter hints) and support for manipulating Urbit nouns (atoms and cells) within C.

Make a development branch for the jet changes first:

$ cd ~/jetting/vere$ git branch example-jet$ git checkout example-jet

Jet hints must provide a trail of symbols for the interpreter to know how to match the Hoon arms to the corresponding C code. Think of these as breadcrumbs. Here we have a two-deep scenario. Specifically, we mark the outermost arm with ~% and an explicit reference to the Arvo core (the parent of part). We mark the inner arms with ~/ because their parent symbol can be determined from the context. The @tas token will tell the runtime (Vere) which C code matches the arm. All symbols in the nesting hierarchy must be included.

~% %trig ..part ~|%++ factorial~/ %factorial|= x=@ud ^- @ud...--

We also need to add appropriate handles for the C code. This consists of several steps:

- Register the jet symbols and function names in

tree.c. - Declare function prototypes in headers

q.handw.h. - Produce functions for compilation and linking in the

pkg/noun/jets/edirectory.

The first two steps are fairly mechanical and straightforward.

Register the jet symbols and function names. A jet registration may be carried out at in point in tree.c. The registration consists of marking the core in the Hoon source and including the name in the C source.

/* Jet registration of ++factorial arm under trig */static u3j_harm _140_hex__trig_factorial_a[] = {{".2", u3we_trig_factorial, c3y}, {}};/* Associated hash */static c3_c* _140_hex__trig_factorial_ha[] = {"903dbafb8e59427eced0b35379ad617c2eb6083a235075e9cdd9dd80e732efa4",0};static u3j_core _140_hex__trig_d[] ={ { "factorial", 7, _140_hex__trig_factorial_a, 0, _140_hex__trig_factorial_ha },{}};static c3_c* _140_hex__trig_ha[] = {"0bac9c3c43634bb86f6721bbcc444f69c83395f204ff69d3175f3821b1f679ba",0};/* Core registration by token for trig */static u3j_core _140_hex_d[] ={ /* ... pre-existing jet registrations ... */{ "trig", 31, 0, _140_hex__trig_d, _140_hex__trig_ha },{}};

The numeric component of the title, 140, indicates the Hoon Kelvin version. Library jets of this nature are registered as hex jets, meaning they live within the Arvo core. Other, more inner layers of %zuse and %lull utilize pen and other three-letter jet tokens. (These are loosely mnemonic from Greek antecedents.) The core is conventionally included here, then either a d suffix for the function association or a ha suffix for a jet hash. (Jet hashes are a way of “signing” code. They are not as of this writing actively used by the binary runtimes.) Arms are marked with _a and child cores with _d. The structs used are defined in jets.h.

The particular flavor of C mandated by the Vere kernel is quite lapidary, particularly when shorthand functions (such as u3z) are employed. In this code, we see the following u3 elements:

c3_c, the platform C 8-bitchartypec3y, loobean true,%.y(similarlyc3n, loobean false,%.n)u3j_core, C representation of Hoon/Nock coresu3j_harm, an actual C jet ("Hoon arm")

The numbers 7 and 31 refer to relative core addresses. In most cases—unless you're building a particularly complicated jet or modifying %zuse or %lull—you can follow the pattern laid out here. ".2" is a label for the axis in the core [battery sample], so just the battery. The text labels for the |% core and the arm are included at their appropriate points. Finally, the jet function entry point u3we_trig_factorial is registered.

For more information on u3, please check out the u3 summary below or the official documentation at “u3: Land of Nouns”.

Declare function prototypes in headers.

A u3w function is always the entry point for a jet. Every u3w function accepts a u3noun (a Hoon/Nock noun), validates it, and invokes the u3q function that implements the actual logic. The u3q function needs to accept the same number of atoms as the defining arm (since these same values will be extricated by the u3w function and passed to it).

In this case, we have cited u3we_trig_factorial in tree.c and now must declare both it and u3qe_trig_factorial:

In w.h:

u3_noun u3we_trig_factorial(u3_noun);

In q.h:

u3_noun u3qe_trig_factorial(u3_atom);

Produce functions for compilation and linking.

Given these function prototype declarations, all that remains is the actual definition of the function. Both functions will live in their own file; we find it the best convention to associate all arms of a core in a single file. In this case, create a file pkg/noun/jets/e/trig.c and define all of your trig jets therein. (Here we show ++factorial only.)

As with ++add, we have to worry about direct and indirect atoms when carrying out arithmetic operations, prompting the use of GMP mpz operations.

/* jets/e/trig.c***/#include "all.h"#include <stdio.h> // helpful for debugging, removable after development/* factorial of @ud integer*/u3_nounu3qe_trig_factorial(u3_atom a) /* @ud */{fprintf(stderr, "u3qe_trig_factorial\n\r"); // DELETE THIS LINE LATERif (( 0 == a ) || ( 1 == a )) {return 1;}else if ( _(u3a_is_cat(a))) {c3_d c = ((c3_d) a) * ((c3_d) (a-1));return u3i_chubs(1, &c);}else {mpz_t a_mp, b_mp;u3r_mp(a_mp, a);mpz_sub(b_mp, a_mp, 1);u3_atom b = u3qe_trigrs_factorial(u3i_mp(b_mp));u3r_mp(b_mp, b);mpz_mul(a_mp, a_mp, b_mp);mpz_clear(b_mp);return u3i_mp(a_mp);}}u3_nounu3we_trig_factorial(u3_noun cor){fprintf(stderr, "u3we_trig_factorial\n\r"); // DELETE THIS LINE LATERu3_noun a;if ( c3n == u3r_mean(cor, u3x_sam, &a, 0) ||c3n == u3ud(a) ){return u3m_bail(c3__exit);}else {return u3qe_trig_factorial(a);}}

This code merits ample discussion. Without focusing on the particular types used, read through the logic and look for the skeleton of a standard simple factorial algorithm.

u3r operations are used to extract Urbit-compatible types as C values.

u3i operations wrap C values back into Urbit-compatible types.

u3 Overview

Before proceeding to compose a more complicated floating-point jet, we should step back and examine the zoo of u3 functions that jets use to formally structure atom access and manipulation.

u3 Functions

u3 defines a number of functions for extracting data from Urbit types into C types for ready manipulation, then wrapping those same values back up for Urbit to handle. These fall into several categories:

| Prefix | Mnemonic | Source File | Example of Function |

|---|---|---|---|

u3a_ | Allocation | allocate.c | u3a_malloc |

u3e_ | Event (persistence) | events.c | u3e_foul |

u3h_ | Hash table | hashtable.c | u3h_put |

u3i_ | Imprisonment (noun construction) | imprison.c | |

u3j_ | Jet control | jets.c | u3j_boot |

u3k_ | Jets (transfer semantics, C arguments) | [a-g]/*.c | |

u3l_ | Logging | log.c | u3l_log |

u3m_ | System management | manage.c | u3m_bail |

u3n_ | Nock computation | nock.c | u3nc |

u3q_ | Jets (retain semantics, C arguments) | [a-g]/*.c | |

u3r_ | Retrieval; returns on error | retrieve.c | u3r_word |

u3t_ | Profiling and tracing | trace.c | u3t |

u3v_ | Arvo operations | vortex.c | u3v_reclaim |

u3w_ | Jets (retain semantics, Nock core argument) | [a-g]/*.c | |

u3x_ | Retrieval; crashes on error | xtract.c | u3x_cell |

u3z_ | Memoize | zave.c | u3z_uniq |

u3 Nouns

The u3 system allows you to extract Urbit nouns as atoms or cells. Atoms may come in one of two forms: either they fit in 31 bits or less of a 32-bit unsigned integer, or they require more space. In the former case, you will use the singular functions such as u3r_word and u3a_word to extract and store information. If the atom is larger than this, however, you need to treat it a bit more like a C array, using the plural functions u3r_words and u3a_words. (For native sizes larger than 32 bits, such as double-precision floating-point numbers, replace word with chub in these.) Confusing a 31-bit-or-less integer with a 32+-bit integer means confusing a value with a pointer! Bad things will happen!

An audit of the jet source code shows that the most commonly used u3 functions include:

u3a_freefrees memory allocated on the loom (Vere memory model).u3a_mallocallocates memory on the loom (Vere memory model). (Never use regular Cmallocinu3.)u3i_byteswrites an array of bytes into an atom.u3i_chubis the ≥32-bit equivalent ofu3i_word.u3i_chubsis the ≥32-bit equivalent ofu3i_words.u3i_wordwrites a single 31-bit or smaller atom.u3i_wordswrites an array of 31-bit or smaller atoms.u3m_bailproduces an error and crashes the process.u3m_pprints a message and au3noun.u3r_atretrieves data values stored at locations in the sample.u3r_byteretrieves a byte from within an atom.u3r_bytesretrieves multiple bytes from within an atom.u3r_cellproduces a cell[a b].u3r_chubis the >32-bit equivalent ofu3r_word.u3r_chubsis the >32-bit equivalent ofu3r_words.u3r_meandeconstructs a noun by axis address.u3r_metreports the total size of an atom.u3r_trelfactors a noun into a three-element cell[a b c].u3r_wordretrieves a value from an atom as a Cuint32_t.u3r_wordsis the multi-element (array) retriever likeu3r_word.

u3 Samples

Defining jets which have a different sample size requires querying the correct nodes of the sample as binary tree:

1. 1 argument → u3x_sam 2. 2 arguments → u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_3 3. 3 arguments → u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_6, u3x_sam_7 4. 4 arguments → u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_6, u3x_sam_14, u3x_sam_15 5. 5 arguments → u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_6, u3x_sam_14, u3x_sam_30, u3x_sam_31 6. 6 arguments → u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_6, u3x_sam_14, u3x_sam_30, u3x_sam_62, u3x_sam_63

A more complex argument structure requires grabbing other entries; e.g.,

|= [u=@lms [ia=@ud ib=@ud] [ja=@ud jb=@ud]]

requires

u3x_sam_2, u3x_sam_12, u3x_sam_13, u3x_sam_14, u3x_sam_15

Exercise: Review Jet Code

We commend to the reader the exercise of selecting particular Hoon-language library functions provided with the system, such as

++cut, locating the corresponding jet code in:and learning in detail how particular operations are realized in

u3C. Note in particular that jets do not need to follow the same solution algorithm and logic as the Hoon code; they merely need to reliably produce the same result.

Jet Composition: Floating-Point ++factorial

Let us examine jet composition using a more complicated floating-point operation. The Urbit runtime uses SoftFloat↗ to provide a reference software implementation of floating-point mathematics. This is slower than hardware FP but more portable.

This library lib/trig-rs.hoon provides a few transcendental functions useful in many mathematical calculations. The ~% "sigcen" rune registers the jets (with explicit arguments, necessary at the highest level of inclusion). The ~/ "sigfas" rune indicates which arms will be jetted.

/lib/trig-rs.hoon

:: Transcendental functions library, compatible with @rs::=/ tau .6.28318530717=/ pi .3.14159265358=/ e .2.718281828=/ rtol .1e-5~% %trig ..part ~|%:: Factorial, $x!$::++ factorial~/ %factorial|= x=@rs ^- @rs=/ t=@rs .1|- ^- @rs?: =(x .0) t?: =(x .1) t$(x (sub:rs x .1), t (mul:rs t x)):: Absolute value, $|x|$::++ absolute|= x=@rs ^- @rs?: (gth:rs x .0)x(sub:rs .0 x):: Exponential function, $\exp(x)$::++ exp~/ %exp|= x=@rs ^- @rs=/ rtol .1e-5=/ p .1=/ po .-1=/ i .1|- ^- @rs?: (lth:rs (absolute (sub:rs po p)) rtol)p$(i (add:rs i .1), p (add:rs p (div:rs (pow-n x i) (factorial i))), po p):: Integer power, $x^n$::++ pow-n~/ %pow-n|= [x=@rs n=@rs] ^- @rs?: =(n .0) .1=/ p x|- ^- @rs?: (lth:rs n .2)p::~& [n p]$(n (sub:rs n .1), p (mul:rs p x))--

We will create a generator which will pull the arms and slam each gate such that we can assess the library's behavior. Later on we will create unit tests to validate the behavior of both the unjetted and jetted code.

/gen/trig-rs.hoon

/+ *trig-rs!::- %say|= [[* eny=@uv *] [x=@rs n=@rs ~] ~]::~& (factorial n)~& (absolute x)~& (exp x)~& (pow-n x n)[%verb ~]

We will further define a few unit tests as checks on arm behavior:

/tests/lib/trig-rs.hoon

/+ *test, *trig-rs::::::::|%++ test-factorial ^- tang;: weld%+ expect-eq!> .1!> (factorial .0)%+ expect-eq!> .1!> (factorial .1)%+ expect-eq!> .120!> (factorial .5)%+ expect-eq!> .720!> (factorial .6)==--

Jet Composition

As before, the jet hints must provide a breadcrumb trail of symbols for the interpreter to know how to match the Hoon arms to the corresponding C code.

~% %trig-rs ..part ~|%++ factorial~/ %factorial|= x=@rs ^- @rs...++ exp~/ %exp|= x=@rs ^- @rs...++ pow-n~/ %pow-n|= [x=@rs n=@rs] ^- @rs...--

- Register the jet symbols and function names in

tree.c. - Declare function prototypes in headers

q.handw.h. - Produce functions for compilation and linking in the

pkg/noun/jets/edirectory.

Register the jet symbols and function names.

A jet registration may be carried out at any point in tree.c. The registration consists of marking the core

In pkg/noun/jets/tree.c:

/* Jet registration of ++factorial arm under trig-rs */static u3j_harm _140_hex__trigrs_factorial_a[] = {{".2", u3we_trigrs_factorial, c3y}, {}};/* Associated hash */static c3_c* _140_hex__trigrs_factorial_ha[] = {"903dbafb8e59427eced0b35379ad617c2eb6083a235075e9cdd9dd80e732efa4",0};static u3j_core _140_hex__trigrs_d[] ={ { "factorial", 7, _140_hex__trigrs_factorial_a, 0, _140_hex__trigrs_factorial_ha },{}};static c3_c* _140_hex__trigrs_ha[] = {"0bac9c3c43634bb86f6721bbcc444f69c83395f204ff69d3175f3821b1f679ba",0};/* Core registration by token for trigrs */static u3j_core _140_hex_d[] ={ /* ... pre-existing jet registrations ... */{ "trig-rs", 31, 0, _140_hex__trigrs_d, _140_hex__trigrs_ha },{}};

Declare function prototypes in headers.

We must declare u3we_trigrs_factorial and u3qe_trigrs_factorial:

In w.h:

u3_noun u3we_trigrs_factorial(u3_noun);

In q.h:

u3_noun u3qe_trigrs_factorial(u3_atom);

Produce functions for compilation and linking.

Given these function prototype declarations, all that remains is the actual definition of the function. Both functions will live in their own file; we find it the best convention to associate all arms of a core in a single file. In this case, create a file pkg/noun/jets/e/trig-rs.c and define all of your trig-rs jets therein. (Here we show ++factorial only.)

pkg/noun/jets/e/trig-rs.c

/* jets/e/trig-rs.c***/#include "all.h"#include <softfloat.h> // necessary for working with software-defined floats#include <stdio.h> // helpful for debugging, removable after development#include <math.h> // provides library fabs() and ceil()union sing {float32_t s; //struct containing v, uint_32c3_w c; //uint_32float b; //float_32, compiler-native, useful for debugging printfs};/* ancillary functions*/bool isclose(float a,float b){float atol = 1e-6;return ((float)fabs(a - b) <= atol);}/* factorial of @rs single-precision floating-point value*/u3_nounu3qe_trigrs_factorial(u3_atom u) /* @rs */{fprintf(stderr, "u3qe_trigrs_factorial\n\r"); // DELETE THIS LINE LATERunion sing a, b, c, e;u3_atom bb;a.c = u3r_word(0, u); // extricate value from atom as 32-bit wordif (ceil(a.b) != a.b) {// raise an error if the float has a nonzero fractional partreturn u3m_bail(c3__exit);}if (isclose(a.b, 0.0)) {a.b = (float)1.0;return u3i_words(1, &a.c);}else if (isclose(a.b, 1.0)) {a.b = (float)1.0;return u3i_words(1, &a.c);}else {// naive recursive algorithmb.b = a.b - 1.0;bb = u3i_words(1, &b.c);c.c = u3r_word(0, u3qe_trig_factorial(bb));e.s = f32_mul(a.s, c.s);u3m_p("result", u3i_words(1, &e.c)); // DELETE THIS LINE LATERreturn u3i_words(1, &e.c);}}u3_nounu3we_trigrs_factorial(u3_noun cor){fprintf(stderr, "u3we_trigrs_factorial\n\r"); // DELETE THIS LINE LATERu3_noun a;if ( c3n == u3r_mean(cor, u3x_sam, &a, 0) ||c3n == u3ud(a) ){return u3m_bail(c3__exit);}else {return u3qe_trigrs_factorial(a);}}

This code deviates from the integer implementation in two ways: because all @rs atoms are guaranteed to be 32-bits, we can assume that c3_w can always contain them; and we are using software-defined floating-point operations with SoftFloat.

We have made use of u3r_word to convert a 32-bit (really, 31-bit or smaller) Hoon atom (@ud) into a C uint32_t or c3_w. This unsigned integer may be interpreted as a floating-point value (similar to a cast to @rs) by the expedient of a C union, which allows multiple interpretations of the same bit pattern of data; in this case, as an unsigned integer, as a SoftFloat struct, and as a C single-precision float.

f32_mul and its sisters (f32_add, f64_mul, f128_div, etc.) are floating-point operations defined in software (Berkeley SoftFloat↗). These are not as efficient as native hardware operations would be, but allow Urbit to guarantee cross-platform compatibility of operations and not rely on hardware-specific implementations. Currently all Urbit floating-point operations involving @r values use SoftFloat.

Compiling and Using the Jet

With this one jet for ++factorial in place, compile the jet and take note of where Nix produces the binary.

$ make

Copy the affected files back into the ship's pier:

$ cp base/lib/trig-rs.hoon zod/base/lib$ cp base/gen/trig-rs.hoon zod/base/gen

Restart your fakezod using the new Urbit binary and synchronize these to the %home desk:

> |commit %base

If all has gone well to this point, you are prepared to test the jet using the %say generator from earlier:

> +trig 5120

Among the other output values, you should observe any stderr messages emitted by the jet functions each time they are called.

pkg/noun/jets/e/trig.c

/* integer power of @rs single-precision floating-point value*/u3_nounu3qe_trigrs_pow_n(u3_atom x, /* @rs */u3_atom n) /* @rs */{fprintf(stderr, "u3qe_trig_pow_n\n\r");union sing x_, n_, f_;x_.c = u3r_word(0, x); // extricate value from atom as 32-bit wordn_.c = u3r_word(0, n);f_.b = (float)pow(x_, n_);return u3i_words(1, &f_.c);}u3_nounu3w_trigrs_pow_n(u3_noun cor){fprintf(stderr, "u3w_trig_pow_n\n\r");u3_noun a, b;if ( c3n == u3r_mean(cor, u3x_sam_2, &a,u3x_sam_3, &b, 0) ||c3n == u3ud(a) || c3n == u3ud(b) ){return u3m_bail(c3__exit);}else {return u3q_trigrs_pow_n(a, b);}}

The type union sing remains necessary to easily convert the floating-point result back into an unsigned integer atom.

Exercise: Implement the Other Jets

We leave the implementation of the other jets to the reader as an exercise. (Please do not skip this: the exercise will both solidify your understanding and raise new important situational questions.)

Again, the C jet code need not follow the same logic as the Hoon source code; in this case, we simply use the built-in

math.hpowfunction. (We could—arguably should—have used SoftFloat-native implementations, but that is more involved than this tutorial intends.)

Jetting the Kernel

Hoon jets are compiled into the Vere binary for distribution with the Urbit runtime. Per current development policy, this is the only way to actually share jets with other developers.

Jets are registered with the runtime so that Vere knows to check whether a particular jet exists when it encounters a marked Hoon arm.

~/sigfas registers a jet simply (using defaults).~%sigcen registers a jet with all arguments specified.

Typically we use ~/ sigfas to register jets within a core under the umbrella of a ~% sigcen registration. For instance, ++add is registered under the Kelvin tag of hoon.hoon:

~% %k.140 ~ ~ ::|%++ hoon-version +-- =>~% %one + ~|%++ add~/ %add|= [a=@ b=@]^- @?: =(0 a) b$(a (dec a), b +(b))

As a generic example, let us consider three nested arms within cores. We intend to jet only ++ccc, but we need to give Vere a way of tracking the jet registration for all containing cores.

++ aaa~% %aaa ..is ~...++ bbb~/ %bbb++ ccc~/ %ccc|= dat=@^- pont=+ x=(end 3 w a)=+ y=:(add (pow x 3) (mul a x) b)=+ s=(rsh 3 32 dat):- x?: =(0x2 s) y?: =(0x3 s) y~| [`@ux`s `@ux`dat]!!

We hint ++ccc with %ccc and add a trail of hints up the enclosing tree of arms. ~/ sigfas takes only the term symbol used to label the hint because it knows the context, but ~% sigcen needs two more fields: the parent jet and some core registration information (which is often ~ null). We here use the parent of ..is, a system-supplied jet, as the parent jet. Since ++is is an arm of the Arvo core, ..is is a reference to the entire Arvo core. The whole Arvo core is hinted with the jet label %hex, which is used as the parent for all the top-level jet hints in %zuse.

When hinting your own code, make sure to hint each nesting arm. Skipping any nesting core will result in the jet code not being run.

You do not need to provide C implementations for everything you hint. In the above, we hint %aaa, %bbb, and %ccc—even if our intent is only to jet ++ccc.

Editing the C Source Code

Having hinted our Hoon, we now need to write the matching C code. If we don't, there isn't a problem—hinting code merely tells the interpreter to look for a jet, but if a jet is not found, the Hoon still runs just fine.

This whole process recapitulates what you've done above, but in a generic way.

There are two distinct tasks to be done C-side:

- Write the jet.

- Register the jet.

For each jet you will write one u3we() function and one u3qe() function.

Edit the C Source Code to Add Registration

Edit the header file

include/jets/w.hto have a declaration for each of youru3we()functions. Everyu3we()function looks the same, e.g.u3_noun u3we_xxx(u3_noun);Edit the header file

~/jetting/urbit/pkg/urbit/include/jets/q.hto have a declaration for youru3qe()function.u3qe()functions can differ from each other, taking distinct numbers ofu3_nounsand/oru3_atoms, e.g.u3_noun u3qe_yyy(u3_atom, u3_atom);u3_noun u3qe_zzz(u3_noun, u3_noun, u3_atom, u3_atom);Create a new

.cfile to hold your jets; both theu3we_()andu3qe_()functions go in the same file, for instance~/jetting/urbit/pkg/noun/jets/e/secp.c. The new file should include at least the following three things:#include "all.h"- the new

u3we()function - the new

u3qe()function

Edit

~/jetting/urbit/pkg/urbitjets/tree.cto register the jet.

In the Hoon code we hinted some leaf node functions (%ccc for ++ccc in our example) and then hinted each parent node up to the root %aaa/++aaa). We need to replicate this structure in C. Here's example C code to jet our above example Hoon:

// 1: register a C func u3we_ccc()static u3j_harm _143_hex_hobo_reco_d[] ={{".2", u3we_ccc, c3y},{}};// 2: that implements a jet for Hoon arm 'ccc'static u3j_core _143_hex_hobo_bbb_d[] ={{ "ccc", _143_hex_hobo_ccc_d },{}};// 3: ... that is inside a Hoon arm 'bbb'static u3j_core _143_hex_hobo_hobo_d[] ={{ "bbb", 0, _143_hex_hobo_bbb_d },{}};// 4: ... that is inside a Hoon arm 'aaa'static u3j_core _143_hex_d[] ={ { "down", 0, _143_hex_down_d },{ "lore", _143_hex_lore_a },{ "loss", _143_hex_loss_a },{ "lune", _143_hex_lune_a },{ "coed", 0, _143_hex_coed_d },{ "aes", 0, _143_hex_aes_d },{ "hmac", 0, _143_hex_hmac_d },{ "aaa", 0, _143_hex_hobo_d },{}};

There are 4 steps here. Let's look at each in turn.

Section 1 names the C function that we want to invoke:

u3we_ccc(). The precise manner in which it does this is by putting entries in an array ofu3j_harms. The first one specifies the jet; the second one is empty and serves as a termination to the array, similar to how a C string is null terminated with a zero. The jet registration supplies two fields{".2", u3we_secp}, but this does not initialize all of the fields ofu3j_harm. Other fields can be specified.The first field, with value ".2" in this example, is "arm 2".

".2"labels the axis of the arm in the core. With a%fasthint (~/sigfas ), we're hinting a gate, so the relevant arm formula is always just the entire battery at+2.The second field, with value

u3we_cccin this example, is a function pointer (to the C implementation of the jet).The third field (absent here) is a flag to turn on verification of C jet vs Hoon at run time. It can take value

c3n(which means verify at run time) orc3y(which means don't verify). If not present, it is set to don't verify.There are additional flags; see ~/tlon/urbit/include/noun/jets.h

Section 2 associated the previous jet registration with the name

"ccc". This must be the same symbol used in the Hoon hint. We again have a “null terminated” (metaphorically) list, ending with{}.Section 3 references structure built in step 2 and slots it under

bbb(again, note that this is exactly the same symbol used in the hinting in Hoon).The line in section 2

{ "ccc", _143_hex_hobo_ccc_a },looks very similar to the line in section 3

{ "bbb", 0, _143_hex_hobo_bbb_d },But note that the line in section 2 fill in the first 2 fields in the struct, and the line in section 3 fills in the first three fields. Section 2 is registering an array of

u3j_harm, i.e. is registering an actual C jet.Section 3 specifies

0for the array ofu3j_harmand is instead specifying an array ofu3j_core, i.e. it is registering nesting of another core which is not a leaf node.Section 4 is much like section 3, but it's the root of this particular tree. Section 4 is also an example of how a given node in the jet registration tree may have multiple children.

You should be able to register jets whether your nesting is 2 layers deep, 3 (like this example), or more. You should also be able to register multiple jets at the same nesting level (e.g. a function u3we_ddd() which is a sibling of u3we_ccc() inside data structure _143_hex_hobo_reco_d[] ).

Edit the C Source Code to Add the u3we_() Function

There are two C functions per jet, because separation of concerns is a good thing.

The first C function—named u3we_xxx()—unpacks arguments from the Hoon code and gets them ready.

The second C function -- named u3qe_xxx()—takes those arguments and actually performs the operations that parallel the Hoon code being jetted.

Let's write the u3we_xxx() function first. This function accepts one argument, of type u3_noun. This is the same type as a Hoon noun (*). This one argument is the payload. The payload is a tree, obviously.

The payload consists of (on the right branch) the context (you'd think of “global variables and available methods”, if analogies to other programming languages were allowed!) and on the left branch the sample (the arguments to this particular function call).

Your u3we_xxx() function does one thing: unpacks the sample from cor, sanity checks them, and passes them to the u3qe_xxx() function.

To unpack the sample, we use the function u3r_mean() to do this, thusly:

u3_noun arg_a, arg_b, arg_c ... ;u3r_mean(cor,axis_a, & arg_a,axis_b, & arg_b,axis_c, & arg_c...0)

If we want to to assign the data located at axis 3 of cor to arg_a, we'd set axis_a = 3.

u3r_mean() takes varargs↗, so we can pass in as many axis/return-argument pairs as we wish, terminated with a 0. You saw above how to pull the sample arguments out of the right-descending trees (because a linked list is a degenerate case of a tree).

If the Hoon that you're jetting looks like this

++ make-k~/ %make-k=, mimes:html|= [aaa=@ bbb=@ ccc=@]

In the C code you'd fetch them out of the payload with

u3r_mean(cor,u3x_sam_2, & arg_aaa,u3x_sam_5, & arg_bbb,u3x_sam_6, & arg_ccc...0)

If you're confident, go ahead and write code. If you want to inspect your arguments to see what's going on, you can pretty print the sample.

You could in theory inspect/pretty-print the noun by calling

u3m_p("description", cor); :: DO NOT DO THIS !!!

… but you don't want to do this, because, recall, cor contains the entire context.

Do instead, perhaps,

c3_o ret;u3_noun sample;ret = u3r_mean(sample, u3x_sam_1, &sample, 0);fprintf(stderr, "ret = %i\n\r", ret); // we want ret = 0 = yesu3m_p("sample", sample); // pretty print the entire sample

After our C function pulls out the arguments it needs to typecheck them.

If arg_a is supposed to be a atom, trust but verify:

u3ud(arg_a); // checks for atomicity; alias for u3a_is_atom()

If it's supposed to be a cell:

u3du(arg_a); // checks for cell-ness

There are other tests you might need to use

u3a_is_cat() // check whether the noun is a direct atom (31 bits or less)u3a_is_dog() // check whether the noun is an indirect noun (32+ bits)u3a_is_pug() // check whether noun is indirect atomu3a_is_pom() // check whether noun is indirect cell

All of these tests return Hoon loobeans (yes 0/no 1 vs. TRUE/FALSE), so check return values vs c3n / c3y. If any of these u3_mean(), u3ud() etc return u3n you have an error and should return

return u3m_bail(c3__exit);

Otherwise, pass the arguments into your inner jet function and return the results of that.

Edit the C Source Code to Add the u3qe_() Function

Unpacking Nouns

The u3qe_xxx() function is the real jet—the C code that replaces the Hoon.

First, you may need to massage your inputs a bit to get them into types that you can use.

You have received a bunch of u3_nouns or u3_atoms, but you presumably want to do things in a native C/non-Hoon manner: computing with raw integers, etc.

A u3_noun will want to be further disassembled into atoms.

A u3_atom represents a simple number, but the implementation may or may not be simple. If the value held in the atom is 31 bits or less, it's stored directly in the atom. If the value is 32 bits the atom holds a pointer into the loom where the actual value is stored. ( see Nouns )

You don't want to get bogged down in the details of this—you just want to get data out of your atoms.

If you know that the data fits in 32 bits or less, you can use

u3r_word(c3_w a_w, u3_atom b);

If it is longer than 32 bits, use

u3r_words(c3_w a_w, c3_w b_w, c3_w* c_w, u3_atom d);

or

u3r_bytes(c3_w a_w, c3_w b_w, c3_y* c_y, u3_atom d)

If you need to get the size, use

u3r_met(3, a);

Cells have their own set of characteristic functions for accessing interior nouns: u3r_cell, u3r_trel, u3r_qual, u3h, u3t, and the like.

The actual meat of the function is up to you. What is the function supposed to do for Hoon?

Packing Nouns

Now we move on to return semantics.

First, you can transfer raw values into nouns using

u3_noun u3i_words(c3_w a_w, const c3_w* b_w)

and you can build cells out of nouns using

u3nc(); // pairu3nt(); // tripleu3nq(); // quad

There are two facets here:

Data format. If the Hoon is expected to return a single atom (e.g. if the Hoon looks like this:)

++ make-k~/ %make-k|= [has=@uvI prv=@] :: <---- input parguments^- @ :: <---- return value is a single value of type '@' (atom)...then your C code—at least when you're stubbing it out—can do something like

return(123);Or, if you want to create an atom more formally, you can build it like this

// this variable is on the stack and will disappearunsigned char nonce32[32];// this allocates an indirect (> 31 bits) atom in the loom,// does appropriate reference count, and returns the 32 bit handle to the atomu3_noun nonce = u3i_words(8, (const c3_w*) nonce32);// this returns the 32 bit handle to the atomreturn(nonce);If, on the other hand, your Hoon looks like

++ ecdsa-raw-sign~/ %ecdsa-raw-sign|= [has=@uvI prv=@] :: <---- input parguments^- [v=@ r=@ s=@] :: <---- return value is a cell...ending your C code with

return(123);is wrong and will result in a runtime error because you are returning a single atom, instead of a tuple containing three atoms.

Instead do one of these:

return(u3nc(a, b)); // for two atomsreturn(u3nt(a, b, c)); // for three atomsreturn(u3nq(a, b, c, d)); // for four atomsIf you need to return a longer tuple, you can compose your own. Look at the definitions of these three functions and you will see that they are just recursive calls to the cell constructor

u3i_cell()e.g.u3i_cell(a, u3i_cell(b, u3i_cell(c, d));This implies that, to create a list instead of a cell, you will need to append

u3_nulto the appropriately-sized tuple constructor:return(u3nt(a, b, u3_nul)); // for two atoms as a listMemory allocation. Understanding the memory model, allocation, freeing, and ownership ('transfer' vs 'retain' semantics) is important. More information is available in the “Nouns” docs.

Pills

A pill is a Nock “binary blob”, really a parsed Hoon abstract syntax tree. Pills are used to bypass the bootstrapping procedure for a new ship, and are particularly helpful when jetting code in hoon.hoon, %zuse, %lull, or the main Arvo vanes.

An Urbit ship has to boot into the Arvo kernel—a Nock core with a particular interface. While it would be possible to make some ad-hoc procedure to initialize Arvo, it would be a drastic layering violation and couple Urbit to all sorts of internal implementation details of Arvo and Hoon. In contrast, a pill is basically a serialized set of declarative steps to initialize Arvo.

You don't strictly need to use pills in producing jets in /lib, but it can speed up your development cycle significantly. However, you must use pills when working on the core kernel (hoon.hoon, zuse.hoon, arvo.hoon).

Producing a Pill

Having edited the C code, you now need to compile it to build a new runtime executable.

$ cd ~/jetting/vere$ bazel build :urbit

You need to compile this in C and in Hoon, however. When the Urbit executable runs, the first thing it does is load the complete Arvo operating system. That step is much faster if it can load a jammed pill, where all of the Hoon has already been parsed from text file into Hoon abstract syntax tree, and then compiled from the Hoon into the Nock equivalent.

Critically, this means that if you edit hoon.hoon, zuse.hoon, arvo.hoon, lull.hoon, /sys/vane/ames.hoon, etc., and then restart the executable, you are not running your new code.

The only way to run the new code is to follow the following process:

Start up a new fakeship (typically

~zod) which knows where your edited Arvo files are (although it will not execute them, as discussed above).From the Dojo command line, load the Hoon files and compile them into a

pillfile:> .pill +pill/solid%solid-start%solid-loaded%solid-parsed%solid-compiled%solid-arvo[%solid-kernel 0x6aa7.627e]%arvo-assembly[%solid-veer p=%$ q=/zuse][%tang /~zod/home/~2018.7.25..20.47.51..0027/sys/zuse ~mondyr-rovmes]If this is successful, then you are ready to move forwards. Otherwise, correct the syntax errors and iterate.

Exit the ship with

Ctrl+Dor|exit.Save the pill file.

$ cd ~/jetting$ cp zod/.urb/put/.pill ./mypill.pill

Run the Compiled C/Compiled Hoon Pill

Prepare a new fakezod (you can't use a backup fakezod here because the point is to boot from scratch again):

$ cd ~/jetting$ rm -rf zod$ /path/to/new/urbit -F zod -B ~/tlon/mypill.pill`

If booting takes more than about 90 seconds, you may have created a ‘poison pill’, which hangs things. Try booting without the -B flag, and/or reverting your Hoon changes, generating a new pill based on that, and launching urbit with the known-clean pill. If these steps and boot in <90 seconds, but a boot with a pill created from your own Hoon does not, you have a Hoon bug of some sort.

Hoon bugs that disable booting can be as simple as the wrong number of spaces. Many, but not all of them, will result in compile errors during the .pill +pill/solid step. If your booting takes >90 seconds, abort it, and debug at your Hoon code.

- Inside the Dojo,

|committhe changedhoon.hoonor other system file. It should automatically recompile if correct.

You now have created a galaxy fakezod, on its own detached network, running your own strange variant of the OS.

- Run and test your jetting code, e.g.

(ccc:bbb:aaa 1 2 3).

(As an aside, should you see “biblical” names like noah, this means that you are using a feature of the kernel in a core before it is available. You'll need to move things to a later point in the file or change your code if that happens.)

Testing Jets

All nontrivial code should be thoroughly tested to ensure software quality. To rigorously verify the jet's behavior and performance, we will combine live testing in a single Urbit session, comparative behavior between a reference Urbit binary and our modified binary, and unit testing.

Live spot checks rely on you modifying the generator

trig-rs.hoonand observing whether the jet works as expected.When producing a library, one may use the

-build-filethread to build and load a library core through a face. Two fakezods can be operated side-by-side in order to verify consistency between the Hoon and C code.> =trig-rs -build-file %/lib/trig-rs/hoon> (exp:trig-rs .5)Comparison to the reference Urbit binary can be done with a second development ship and the same Hoon library and generator.

Unit tests rely on using the

-testthread as covered in Hoon School and the testing guide.> -test %/tests/lib/trig-rs ~One of the arguments to the C function registration forces comparison of the results of the Hoon/Nock code and the C jet.

It can take value

c3n(which means to verify the jet's behavior at run time) orc3y(which means to not verify). If not present, it will not verify.Why is

c3y("yes") used to turn OFF verification? Because the flag is actually asking, “Is this jet already known to be correct?”There are integration tests available for the Urbit repository; you should investigate the now-current standard of practice for implementing and including these with your jetted code submission.

Et Cetera

We omit from the current discussion a few salient points:

Reference counting with transfer and retain semantics. (For everything the new developer does outside of real kernel shovel work, one will use transfer semantics.) These are discussed in the “Noun” docs.

The structure of memory: the loom, with outer and inner roads. This is discussed in the “Noun” docs.

Many details of C-side atom declaration and manipulation from the

u3library. These are discussed in the API docs.fprintf-based output should be done usingfprintf()tostderr. Use both\nand\rto achieve line feed (move cursor down one line) and carriage return (move it to the left). You can also useu3l_logwhich does not require\r\n, but should not be used in cases where the IO drivers have not yet been initialized or can no longer be relied upon, e.g. crashing or shutdown.A jet can be partial: it can solve certain cases efficiently but leave others to the Hoon implementation. A

u3w_*jet interface function takes the entire core as one noun argument and returns au3_weakresult. If the return value isu3_none(distinct fromu3_nul,~null), the core is evaluated; otherwise the resulting noun is produced in place of the nock.